I’ve recently been presenting a talk at various groups and conferences; the subject of which is software architecture. The main gist of the talk is around non-functional requirements, but the gathering and design of functional requirements is obviously, also, important. I thought it might be an idea to lay out my thoughts on the concept of a Minimum Viable Product, why I think they’re important, and exactly what they should, and should not, be.

There are two key parts to an MVP, that it should be both minimum, and viable. I appreciate that sounds a bit like it belongs in an episode of BlackAdder, but bear with me…

Minimum Viable

Let’s imagine that we’re writing a program that adds up two numbers - what’s the minimum thing that this program can do, and still be viable? That is, what’s the least about of functionality that we can put into the program, and it still fulfill the requirement?

In a planning, or investigation session, the subject of a user interface may come up. It may, in fact, be necessary to have a UI. The key piece of information that you need here is: why. Why are we creating a program that adds two numbers: what’s the context of the problem? Without that information, there is a real danger that the requirements will spiral out of control; since you have no idea who or what is using the software, you’ll start catering for every possibility.

Let’s take two possible context statements as an example:

We need a program that will add two numbers together; this is because our nuclear reactor needs to establish the exact time to release gas.

(I use nuclear reactor examples a lot, and I always add a disclaimer that I don’t know anything about them, except that the cost of failure is extremely high)

Let’s compare that to:

We are creating a tool to teach small children to add up; we therefore need a program that will display a colourful interactive environment so that the children will be engaged.

Okay - so now you have context, clearly the second problem requires a very different design than the first!

Why Minimum, Though?

MVPs are often linked to a strategy to release software before it is ready. I would argue that this is missing the point.

Every single line of code that you write carries some risk factor, I don’t know what these figures are, but I do know that they are not zero. For the sake of argument, let’s say that the chance of writing a line of code that has a bug (and by that, I mean a line of code that either crashes the program, or has an unintended consequence) is 0.1%. That seems like a fair statistic - for every 100 lines of code, you have a 10% chance of introducing a bug.

Let’s add onto that the fact that every line of code has a testing and support overhead. The testing and support overhead increase as the lines of code do.

Clearly, there are strategies to reduce both, but any system will have these overheads, and they will be greater (or there will be at greater risk of problems occurring) as the size, and therefore complexity of the code increases.

To summarise this, my point here is that creating the minimum amount of functionality, means that you also create the minimum amount of overhead for both testing and support.

Establishing an MVP

Many people will have been in a room where the following kind of list was made up:

- Feature #1

- Feature #2

- Feature #3

MVP is Feature #1 and #2. Feature #3 is a nice-to-have.

The problem here is that, what we are saying is that a system with Feature #1 and #2 is a viable system. If you add Feature #3, you’re incurring additional overhead, but you’re not making the system more viable.

I want to be clear on what I’m saying here: I fully appreciate that, when asked, people will say things like:

Well, we absolutely need feature #1, but we could probably implement a short term manual workaround for Feature #2. Feature #3 would be nice, and it would save time.

So, when I say that the system isn’t more viable, am I missing this point? Well, perhaps, but my argument is this: unless you have a clearly defined goal, you can never reach that goal.

Imagine the following scenario: you decide to commission a house to be built. The architect creates some plans, and the plans say that the house should be (x) big, and the walls should be (y) tall, it should have (z) windows, and so on… Now, what if, in the plans for the house, the architect said that, “if there’s time, add a garage”. The builders are going to look at those plans and assume that a garage is needed - the foundations for a garage will be created, time and effort will go into creating the structure for the garage. However, by the time the house is complete (which takes longer because of that line in the plans), you have sold your car.

My argument is, when you draw out the plans, decide whether you need a garage. If you do, add it to the plans, if not, do not.

Caveat / Disclaimer

To be clear, I’m not saying that, when the business asks for three features, you proudly stand forth and announce they can’t have that, and then lecture them about testing and support overhead. Just the opposite: only the business can decide what constitutes the MVP. However, if the business says that two different states are the MVP (i.e. Feature #1 & #2 are an MVP, but that #3 may be part of that) then you should challenge which of those is the MVP.

Further, once you have decided on an MVP, you should be careful to deliver only that.

Finishing Early

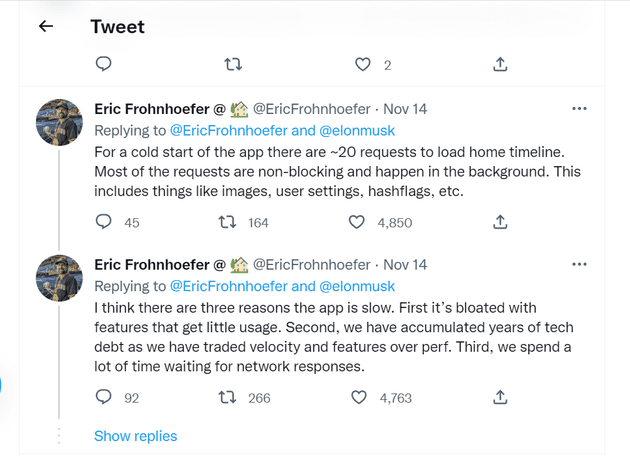

Once the MVP is complete (that is, it’s ready to ship) it should be shipped. Adding more features can cause the code to become bloated:

I’m not making any specific claims about Twitter, this specific engineer, or even Elon Musk, but adding features has a cost beyond the time it takes to actually write that feature. Additionally, there is more value in code that is shipped than code that is sat in a repository somewhere.

Deciding on the MVP

As I’ve stated, I believe it’s incumbent on the business (or a representative of the business - e.g. a product or project manager) to decide what constitutes an MVP; however, it’s equally incumbent on the team implementing that system to determine whether that MVP makes sense.

In the same way that, if a person asked for a house to be built, but dictated that they didn’t want a ground floor, and that the upper floor should simply float in the air, it would be the job of the building architect to point out that the finished product will not stand up; so it should be the job of a software architect to point out that a system designed to take sales orders, but has no payment system, will not allow for the final objective.

Later Changes and Changing an MVP

Obviously, once the MVP is deployed and working, additional features can be added. You may find that such features become more, or less important after the software has been deployed.

That said, what if, prior to deploying the software, the MVP changes? So, we have Feature #1 and #2, but the business decides to re-define the MVP to be #1, #2, and #3. That’s absolutely fine, simply de-define the MVP, and adjust the timelines, and follow the same process again. The key point here is that the business needs to make the decision that Feature #3 is now part of the MVP.